Our History

To 1000 AD

Christianity first came to south-eastern Scotland from the Romans.

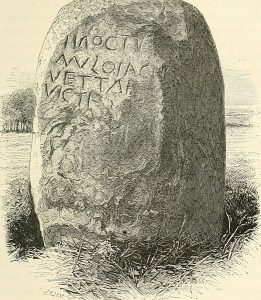

There is a stone called the ‘Cat Stane’ by the runway of Edinburgh airport, marking the burial of a Christian woman called Vetta around 500 AD. St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne grew up near Melrose and the area was home to other early saints like Ebba of Coldingham and Baldred of the Bass Rock. The lands south of the Forth became part of Scotland about 1000 AD and they were part of the diocese of St Andrews. A diocese is a geographical area where the local Christians are led by a bishop. ‘Bishop’, from the Greek word episkopos which means ‘overseer’, has been used since New Testament times of Christian leaders. An Episcopal church is one led by bishops.

Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

The Scottish Church had close connections with the rest of Western Europe and there were a number of reform movements in the sixteenth century, both Catholic and Protestant. Religion and politics, however, combined to divide Scottish Christians at this time; some maintained their links to the Pope, the bishop of Rome, while others remained part of the reformed Church of Scotland.

During the reign of James VI (1566-1625) there were further divisions in the Scottish Church. Some Christians rejected bishops and had a narrow interpretation of the Bible while others valued dignified worship and Christian tradition. James and his son Charles I (1625-1649) encouraged the second group and, as part of his desire to renew the church, Charles founded the diocese of Edinburgh in 1633 and authorised a new Scottish ‘Book of Common Prayer’ in 1637. The first Bishop of Edinburgh was the great scholar William Forbes (1585–1634) who wanted to heal the divisions in the Church.

Resistance to royal policy led to the rejection of bishops in 1638 and the ‘Wars of the Three Kingdoms’ (1639-1651). The bishops were restored with the monarchy in 1660 but after the Dutch Prince William of Orange took power in a revolution in 1688 Alexander Rose, Bishop of Edinburgh, and his fellow bishops refused to give William their unqualified support. The political establishment then made the Church of Scotland ‘presbyterian’, this means that the church is led by committees not by bishops. Most of the Scottish clergy and the majority of the population in the Highlands and North-East remained loyal to the bishops. This marks the start of the Scottish Episcopal Church as a denomination distinct from Roman Catholics, who follow the Pope, and the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

In Edinburgh there were many Episcopalian congregations, such as that which is now Old St Paul’s, and at Kelso, Haddington and other towns Episcopalians continued to worship. The Church was persecuted for its loyalty to the deposed King James VII and his son James VIII and this Jacobite loyalty (from the Latin for James, ‘Jacobus’) led to the Church being reduced, in the words of Sir Walter Scott, to ‘the shadow of a shade’.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

After the defeat of the Jacobite rising in 1745 and the death in 1788 of Charles III (‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’) the Episcopal Church made its peace with the government and most of the laws against it were repealed. Some Episcopalian congregations which were not Jacobite then joined the Church. At Aberdeen in 1784 Samuel Seabury, who had studied medicine at Edinburgh, was consecrated by Scottish Bishops as the first bishop of the American Episcopal Church. This is sometimes seen as the foundation of the worldwide Anglican Communion of which the Scottish Episcopal Church is a member.

The nineteenth century was a period of impressive growth for the Diocese of Edinburgh. Over sixty new churches and missions, a theological college to train clergy and a number of sisterhoods for social work were founded, as were schools and charities. Many of the church buildings in our diocese date from this period, including the mother church of the diocese, St Mary’s Cathedral, which was consecrated in 1879 and became a centre of mission to the working-class areas in the city. The Borders region, previously part of the diocese of Glasgow, was included in the diocese of Edinburgh in 1888. Members of the diocese such as Walter Scott, James Clerk Maxwell and Dean Ramsay made major contributions to the arts, science and religion and the century also saw lay people become involved in the church’s decision-making processes.

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

During the twentieth century new congregations were founded in the suburbs of Edinburgh and elsewhere in the diocese. Episcopalians became involved in chaplaincy work in universities, colleges, hospitals, hospices and places of work and they supported people with AIDS from the 1980s. The Diocese of Edinburgh played a pioneering role in women’s ministry with the first deaconess ordained in 1978, Pam Skelton, the first priests in 1994 and the first female Dean, Susan Macdonald, appointed in 2012. Ecumenical links developed and Richard Holloway, Bishop of Edinburgh 1986-2000, made a major contribution to Scottish intellectual life. In the twenty-first century members of the diocese continue to preach the gospel to Scottish society, work together for justice, peace and the care of creation and build bridges with other faith communities.